| N 18°32.300 E 99°03.000 |

Ban San Khayom Bridge (Th: สะพานบานสันกะยบม / Jp: バンサンカヨム橋) Page 5 of 11 |

Railroad Sta |

| Text | Notes | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

Supplemental Information

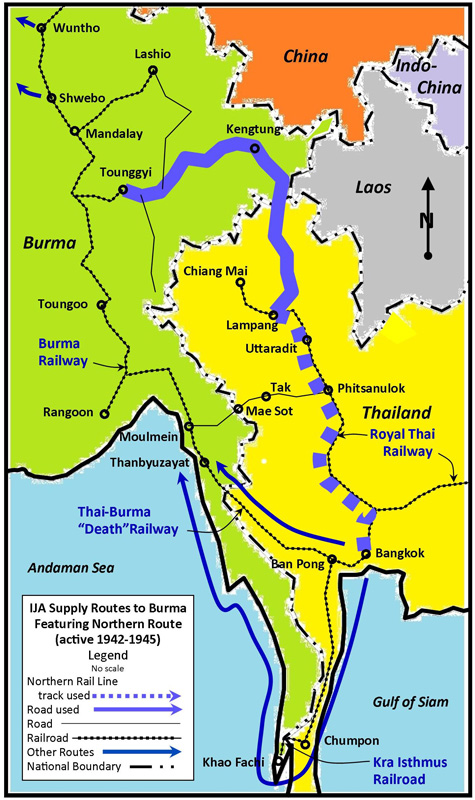

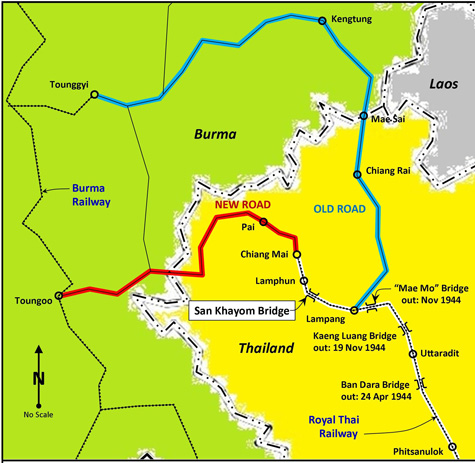

Allied strategy and how the San Khayom bridge fit in[K01] As a preamble, it must be noted that a primary strategic objective of the Allied air effort over Thailand was attacking and disabling railroad bridges [K02]. Doing so on the railroad's Northern Line was deemed critical since it connected Bangkok with Lampang where IJA troops and materiel were transferred to road vehicles, primarily trucks, for transport onward and into Burma.[K03] The connection had been secured in mid-1942 by the IJA and turned over to the Royal Thai Army.[K04] As Allied submarines increasingly pressed Japanese shipping around Southeast Asia, the Japanese developed new land routes into Burma: in addition to the infamous Thai-Burma "Death" Railway and the lesser known Kra Railway,[K04a] the northern route was incorporated into the network.[K05] All three became operational in degrees during the IJA buildup which started in late 1943 for the attempted invasion of India (via Imphal and Kohima).[K06]

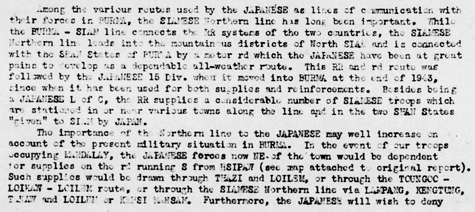

Partial transcription (emphasis added): Along the various routes used by the Japanese as lines of communication with their forces in Burma, the Siamese Northern line has long been important. While the Burma-Siam line [the "Death Railway"] connects the RR systems of the two countries, the Siamese Northern line leads into the mountainous districts of North Siam and is connected with the Shan States of Burma by a motor [road] which the Japanese have been at great pains to develop as a dependable all-weather route. This RR and [road] route was followed by the Japanese 15 [Division] when it moved into Burma at the end of 1943, since when it has been used for both supplies and reinforcements. . . . through the Siamese Northern line via Lampang, Kengtung, Takaw, and Loilem [to a branch railhead at Tounggyi]. . . .

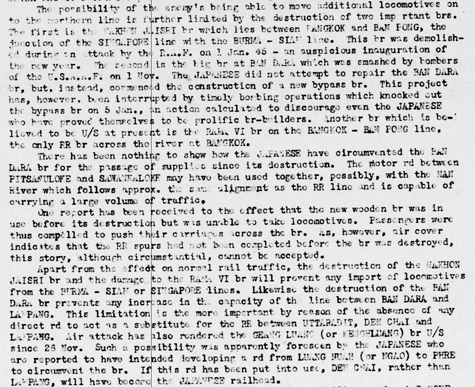

Partial transcription (emphasis added): The possibility of the enemy's being able to move . . . on to the northern line [from the south] is further limited by the destruction of . . . the big [bridge] at Ban Dara which was smashed by bombers of the USAAF on 1 Nov [1944][K09]. . . . . . . the destruction of the Ban Dara [bridge] prevents any increase in the capacity of the line between Ban Dara and Lampang. . . . Air attack has also rendered the [Kaeng Luang bridge unusable] since 26 Nov [1944]. Such a possibility was apparently foreseen by the Japanese who are reported to have intended developing a [road] from [Ngao] to [Phrae] to circumvent the [bridge]. If this [road] has been put into use, Den Chai, rather than Lampang, will have become the Japanese railhead.

Those two bridges were: The more southerly Ban Dara or Paramintara Bridge, aka Paramin (RR stationing 456+988), is located at N17°22.34 E100°04.59.[K10] It had been chosen because it was by far the largest bridge between Bangkok and Lampang, measuring 362m over three spans.[K11] In addition to providing access to the north, it also provided access via a westerly spur to Sawan Khalok, about 30km to the west; that spur had been used in early 1942 for transporting IJA troops north from Bangkok and then west to the border town, Mae Sot, for the invasion of Burma[K12] (from the branch railhead at Sawan Khalok to Mae Sot was still an additional 190km by road). To the north about 95km was the Kaeng Luang Bridge (RR stationing 551+674) --- also known as the Den Chai, for a station about 18km south, or the Huai Mae Ta, for the station next north, or for the stream over which it passed of the same name. Located at N18°02.53 E99°54.96, its 174m length over three spans ranked it the second largest bridge between Bangkok and Lampang. Quoting from the report above, the two bridges were especially important because of: . . . the absence of any direct [road] to act as a substitute for the RR between Uttaradit, Den Chai, and Lampang. Without rail, the distance between Uttaradit and Lampang represented a 157km gap. In addition, outing the two bridges isolated Uttaradit, a major center for rail maintenance services and a large railyard (though the expansion railyard just north at Sila At would not be constructed until 1958).[K13]

The three bridges which had been put out of action very seriously slowed IJA supply movement north to Lampang. The IJA was notably skilled and resourceful in its efforts to repair damaged bridges; however persistent Allied bombing efforts overwhelmed those efforts.[K14] Because there was no alternative road route, rail traffic did continue, primarily with the use of extremely tedious and time-consuming road detours around the non-functional bridges. That also entailed the splitting up of locomotives and rolling stock amongst a resultant four separate railway sections which further reduced efficiency.

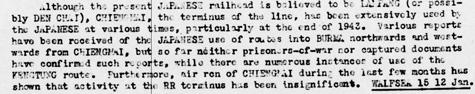

Transcription of the first part of the paragraph: Although the present Japanese railhead is believed to be Lampang (or possibly Den Chai), [Chiang Mai], the terminus of the line, has been extensively used by the Japanese at various times, particularly at the end of 1943. Various reports have been received of the Japanese use of routes into Burma northwards and westwards from [Chiang Mai], . . . .

Around 01 August 1943, the IJA 15th Division was ordered to improve a patchwork of roads, footpaths, and oxcart and elephant trails between Chiang Mai and Toungoo, Burma into a viable motor vehicle road. It was to be the primary road from northwest Thailand to the Burma railway, replacing the much longer existing road from Lampang to Tounggyi, Burma:[K16a]

That existing road on the old route was badly in need of major repair; consequently improvement of the patchwork to make a new road was initially thought to be a better investment. Entering into that evaluation: the route increased reliance of existing railways, which were relatively immune to the rainy season, and the new road was considerably shorter than the old:[K16b]

The project, however, proved too ambitious to fit into the IJA's schedule for the invasion of India and, on 15 November 1943, 15th Division troops destined for Imphal were rerouted to the old, existing road via Lampang.[K17] As a result, various elements of the IJA's 15th Division in the Chiang Mai area gathered at the rail station for transport south to Lampang, to then follow the road north to Mae Sai and beyond.[K18] On 21 December, around 1500 hrs, twenty-nine USAAF 14th Air Force B-24s bombed Chiang Mai Rail Station, destroying the station house, cargo depots, and nearby warehouses, and killing more than 300 people.[K19] It can be surmised that, at some point, a routine Allied recon flight had photographed IJA troops and equipment massing at Chiang Mai rail station. No doubt aerial photo analysts believed the troops were preparing an aggressive move either north or west into Burma. An order to attack would have quickly followed. However, the last of the 15th Division units going to Imphal had left Chiang Mai on 18 Dec 1943,[K19a] three days before the B-29 raid; so the death toll of 300 from the Allied bombing was almost entirely Thai civilians.[K19b] Thus the damage and disruption at the terminus, while devastating, had a much lesser effect on IJA assets than Allied planners had intended. And it contributed to many older Thais harboring a lingering hostility towards Westerners, while maintaining an unqualified friendliness towards Japanese: after all, the Japanese had never bombed northern Thailand. Allied intelligence reports about the results of that raid and subsequent reconnaissance of the Chiang Mai area are not currently available, but it can be assumed that follow-up aerial photos were seen to evidence a major decline in IJA activity around Chiang Mai railway station, for whatever reason. The misperception that Chiang Mai was a potential jumping off point for travel to Burma persisted amongst Allied intel analysts at least into January 1945 as demonstrated by the transcription of the remainder of the paragraph imaged above:[K20] Various reports have been received of the Japanese use of routes into Burma northwards and westwards from [Chiang Mai], but so far neither prisoners-of-war nor captured documents have confirmed such reports, while there are numerous instances of use of the Kengtung route. Furthermore, air [reconnaissance] of [Chiang Mai] during the last few months has shown that activity at the RR terminus has been insignificant.

As the skies over northwest Thailand became Allied "domain",[K21] flight orders apparently routinely included seeking out targets of Two truss bridges in the area west of Lampang to Chiang Mai did suffer shell holes --- the San Khayom, of course, but also the road bridge in Chiang Mai[K25] (demolished in 1966). To be clear, the three bridges south of Lampang which were effectively destroyed, were destroyed by bombing, not strafing. Truss bridges were almost impossible to destroy with strafing --- bombing of abutments and piers was required.[K26] Shell damage to bridge structures was incidental when pilots, pursuing targets of opportunity, fired on rolling stock which was passing over those bridges.

This presentation sets the background for the following review of possible sources for the 20mm holes at Points A and F.

|

K01.^ This was developed in response to questions in LWD's 1522 hrs 04 Mar 2014 Post#2 on Axis History Forum and Lowell Turner's 2306 hrs 07 Mar 2014 post on Tullys Port at CombinedFleet. K02.^ White paper: "American Listing of Military Objectives in Thailand in Reference to Maps: Mandalay, Rangoon, Bangkok. Scale 1:1000000" (India: Headquarters US Air Forces, Tenth US Air Force, 22 Mar 1942) (USAF Archive microfilm reel A8233:pp1269-1272) Young, EM, Aerial Nationalism, p 202. Jackson, Daniel, The Forgotten Squadron, p 93. K03.^ Young, ibid, p 201. K04.^ Young, ibid, p 192. K04a.^ See, esp, Boggett, David, Notes on the Thai-Burma Railway, Part IX, The Kra Isthmus Railway, in Journal of Kyoto Seika University, 27:26-45 K05.^ 戦史叢書 : Vol 15: インパール作戦―ビルマの防衛 K06.^ Senshi Sosho v15, pp 139 ff. K07.^ Composed by author using Microsoft Publisher. Primary source: Senshi Sosho v15, map p 141.

K08.^ Transportation Report: Road, Railroad, and Inland Waterways: Asiatic Area (New Delhi: China-Burma-India Joint Intelligence Collection

Agency, 15-31 Jan 1945)

"Railroads: Siam", p 53

K08a.^ ibid

K09.^ Possible confusion here between the Ban Dara and the Kaeng Luang farther north; the Ban Dara was downed on 24 April 1944* while the Kaeng Luang was downed on 19 November 1944** *Wisarut Bholsithi post#2 in axishistory forum: "Bombing of Southeast Asia" of 14 Jul 2010 12:20.

K10.^ Source: Google Earth. K11.^ Wisarut post in rotfaithai forum of 12 Dec 2007 0959.

K12.^ Sivaram, M, The Road To Delhi (Rutland VT: Tuttle, 1966), pp 55-62.

K13.^ Wikipedia: Uttaradit Railway Station.

K14.^ Transportation Report Road, Railroad, and Inland Waterways: Asiatic Area, ibid, p 54 (USAF Archive microfilm reel A8044:p0557).

K15.^ ibid.

K16.^ Senshi Sosho v15, p 140 (translation).

K16a.^ Maps composed by author using Microsoft Publisher. Primary source: Senshi Sosho v15, map p 141.

K16b.^ ibid

K17.^ Ibid, p 180.

K18.^ Ibid, p 181.

K19.^ 2bangkok forum: history: WWII bombardment of Thai railways. Wisarut post 57 of 30 Oct 2008, 1440 hrs. K19a.^ Senshi Sosho v15, p 181 (translation). K19b.^ This is consistent with Bergin's statement that "More than 300 Thais civilians were killed". (Bob Bergin, CIA Library: Historical Intelligence Vignette: Bob Bergin, The Youngest Operative: A Tale of Initiative Behind Enemy Lines During WW II)

K20.^ Transcription from Transportation Report Road, Railroad, and Inland Waterways: Asiatic Area, ibid, p 54

K20a.^ Extrapolating from CAC post 15 in WWIIF forum on thread "ID of WW2 aircraft guns . . . holing a Thai railway bridge", an interesting alternative explanation for leaving the bridge intact: goods might have been more efficiently attacked at the delivery point, ie, concentrated in the materiel dumps around Chiang Mai airfield. The field did continue to be bombed till at least as late as 28 May 1945. K21.^Young, pp 202, 204. K22.^ Jackson, ibid, p 94. Young, ibid, p 204 K23.^ Observation by RAF post-WW2 veteran Graham Truss, 31 Mar 2014. K24.^ Jackson, ibid, p 94. K25.^ Various discussions with Boonserm Satrabhaya; undated. K26.^ Jackson, ibid, p 94.

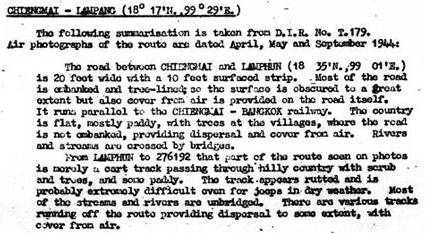

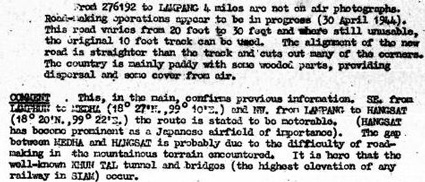

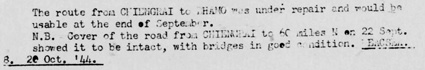

K27.^ Communications in Siam, French Indo-China, and Yunnan (Inter-Service Topographical Department (SSAC), 01 Mar 1945), Siam: Roads, p 7 (USAF Archive microfilm reel A8021: p0165) NB: the "summarization" is taken directly from a previously published detail dated 12 November 1944 in Road and Railroad Communications Report: Asiatic Area (New Delhi: Joint Intelligence Collection Agency, 15-30 Nov 1944).

K27a.^ 276192 on a UTM grid for this area should be: N18°15.725 E99°15.666 (conversion per Montana State University: Convert Geographic Units) This doesn't compare well with data in "Comment", which would seem to imply that 276192 is near Hang Chat on the eastern side of the ridge at the stated: N18°20 E99°22 Assume error in specified UTM. To clarify: the two intermediate locations mentioned, Mae Tha and Hang Chat, were in the lowlands on either side of the Khun Tan mountain ridge, and it was the ridge which constituted the inhospitable terrain. K27b.^ The Pang Lha bridge, erected in 1920. Its tight curves limited speeds to 20‑25kph. Photo originally published in Annual Report of Siamese State Railway BE 2463. Bridge was replaced in Dec 1967. Identification by Wisarut Bholsithi email of 2310 01 Nov 2014. This image is from ThaiVisa website. K27c.^ Bholsithi email, ibid.

K28.^ Bergin, Bob, "Flying Tiger, Burning Bright", Aviation History, July 2008, p 30.

K29.^ Transportation Report Road, Railroad, and Inland Waterways: Asiatic Area (New Delhi: China-Burma-India Joint Intelligence Collection

Agency, 15-31 Oct 1944)

"Railroads: Siam", p 29

K30.^ Need ref (interim: 02300 Route Choice (root))

|