| N18°31.6 E97°56.0 |

Details of Aircraft Losses by Date 13 Apr 1943: IJAAF Warplane at Mae La Luang |

Route 108 |

| Text | Notes | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

13 Apr 1943.

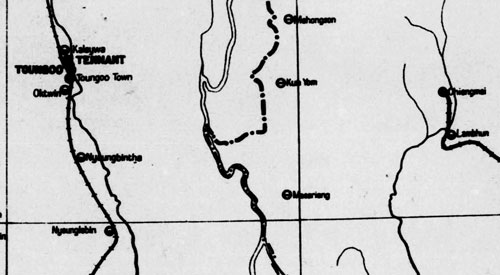

How a Japanese warplane came to make an emergency landing in a relatively remote section of Thailand is not clear. As noted, eye witnesses recalled seeing smoke coming from the plane. The plane's engine may simply have failed. Or the plane might have been damaged in an encounter with an enemy (Allied) aircraft. The plane might have been hit far distance from Mae La Luang and the pilot was able to nurse his ailing plane only as far as that area before having to land. Or perhaps he had to land as quickly as possible after being hit. A larger scale map gives a better idea of the choices that the Japanese pilots apparently had, on the latter basis, for a landing site, with nearby air facilities circled:[6]

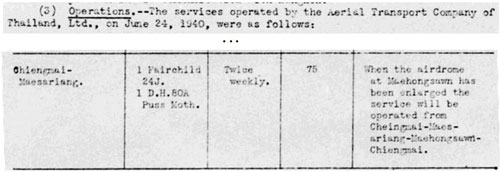

Conditions at those facilities varied, but in an emergency, such would have been of secondary concern. In Burma, airfields at Taungoo, Nyangbintha, and Nyaunglebin[6a] fall within a radius of 150 km of the crash landing. In Thailand, Chiang Mai is 110 km distant with Mae Hong Son at 85 km while Khun Yuam and Mae Sariang are roughly within 40 km. In the case that the plane had been fatally hit or simply lost power suddenly, that both Khun Yuam and Mae Sariang had airstrips implies that the distance from where the plane became disabled and crash landed was less than 40 km. It is also possible that the pilots, relocated from Sumatra to Burma just a month before, were not familiar with the alternative landing sites available. Note that there is a possibility that if an intercept with an enemy aircraft had occurred, it could have been over Thai territory. Thailand was not being targeted by the Allies at this particular time.[6β] As Thailand was an ally of Japan, Japanese aircraft should have had free access to any air space over Thailand. Conversely, the Allies presumably saw Burma and Thailand as essentially one and felt no need to avoid Thai air space while attacking Burmese targets. As shown on the map, support after the crash landing came from the closest major IJAAF air facility, Chiang Mai, 110 km distant. A decision to provide ground assistance from Mae Sariang would have been based on the existence of a biweekly air service which had been running between Mae Sariang and Chiang Mai town since at least Jun 1940, well before the war started:[6b]

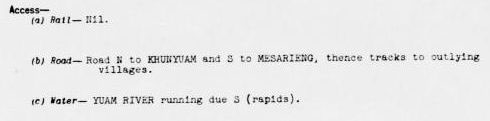

An intelligence report on the Mae Sariang airstrip describes roads providing access to the airstrip as "Road N to KHUNYUAM and S to MESARIENG, thence tracks to outlying villages."[6c]

In other words, the precursor to the section of Thai Route 108 that today connects Mae Sariang east to Hot (then north to Chiang Mai) did not then exist in a condition apparently judged suitable for military use. The two crewmembers were not seriously injured (if at all) in the crash landing, but damage to the aircraft was beyond repair and the crew remained there overseeing disposition of the wreckage for about two months. Food and other essentials were periodically airdropped to the crew by IJAAF aircraft coming from the direction of Chiang Mai. Some of the wreckage was salvaged by a Japanese army unit from Mae Sariang while the remainder was largely destroyed. After the war, one piece of aluminum reputably from the aircraft firewall was hung in the local police station and used to ring on the hour for years. Other pieces, unidentified, were put on display at a local "cultural center". Villagers salvaged pieces of aluminum to make spoons. The above details are undisputed. Unfortunately, they cannot readily be related to existing records of the IJAAF, the Allies, or the Royal Thai Air Force. Nonetheless, a tenuous connection based on circumstantial evidence is developed from IJAAF records as presented by Umemoto coupled with interviews with eye witnesses by Cherdchay Chantawan[6d] and information from Shores. It is emphasized that the scenario which follows is highly speculative.

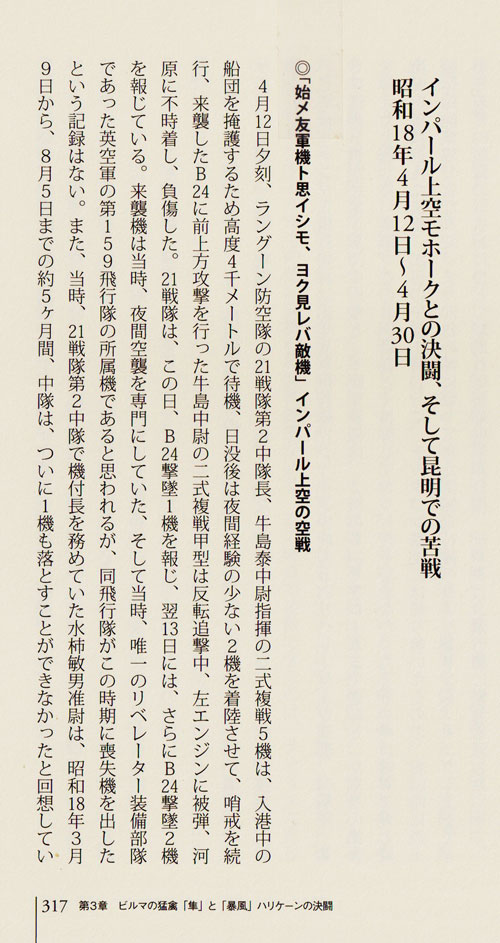

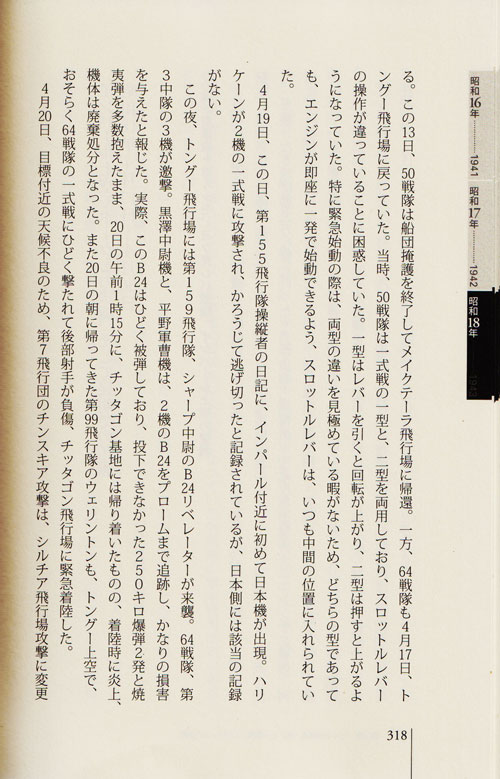

References (in chronological order) Umemoto, 2002[7] Umemoto's seminal work in Japanese tallying events in the air war in Burma does not mention an event at Mae La Luang, nor the more likely, its province, Mae Hong Son. This might be explained by the event occurring in Thailand rather than Burma; but numerous other IJAAF events in northern Thailand are covered --- as examples, Chiang Mai, Lampang, Nakhon Sawan, Uttaradit. However, one IJAAF casualty, whose details admittedly puzzled Umemoto --- when coupled with leads from other sources --- could be "forced-fitted" to the event recorded by eye witnesses on the ground at Mae La Luang. Interviews with witnesses of the crash landing in the town were conducted by Cherdchay Chantawan, one of which was recorded around 2008, and were incorporated into a Japanese language webpage about the event in 2012. Included in the webpage was a photo of an IJAAF Ki-45 fighter. There was no basis in the interviews for picturing that particular model of aircraft; however its two man crew is consistent with eye-witness accounts of a two man crew; there is also a date range given for the event, March plus June-July 1943, though dates recalled in rural Thailand have proven extremely unreliable. However, with that information, I consulted Christopher Shores' Air War for Burma,[8] which provided shortcuts in searching Umemoto's list of events. Shores describes only one IJAAF unit, Sentai 21, as having flown Ki-45 fighters in the Burma Theatre, and dates their presence from Mar 1943 to Jan 1944: equipped with the Ki-45 Kai-ko fighters, the sentai moved from Sumatra to Mingaladon (Rangoon) in March 1943, and left in January 1944.[8a] Umemoto lists four Sentai 21 losses within that time period[9] and one of those four involved a two-man crew surviving a crash landing and a riverbank. The coincidence of these details matching the contents of local interviews (conducted perhaps six years later by Cherdchay) suggests that the two sources are dealing with the same event (Umemoto's book is in Japanese, so there is little likelihood that Cherdchay would have been aware of a similarity in details). Further, while acknowledging my dependence upon Google Translate, I believe that the combination of details involving a two-man crew aircraft crashing / crash landing with minor or no injuries on a riverbank is unique amongst Umemoto's listings --- though other details in Umemoto's listing of this particular event as noted below admittedly do not remotely match. Umemoto dates that event as 12 Apr 1943:[10]

Date: The date is specific and applies to a Sentai 21 mission involving a patrol of Rangoon harbor, but not necessarily to a subsequent crash landing by one of the aircraft in that mission; it falls between the two broadly estimated dates in Cherdchay's interviews of March and June-July 1943. Umemoto's text accompanying the event[11] tells that the sentai sent up a flight of Ki-45s on that date to provide cover for ships coming into Rangoon harbor during an evening. At some point in that evening, the mission was completed and at some later time, whether later that night or the next day is not clear, a Sentai 21 flight encountered and attacked one or more B-24s which Umemoto identifies as from RAF 159 Squadron, though he clearly states this as conjecture since Allied records do not support the encounter. Gunfire from one B-24 damaged a sentai aircraft, which is the subject of this casualty report by Umemoto. The actual time, ie, the hour, of the attack is contentious. Umemoto implies that the attack and the subsequent crash landing occurred during hours of darkness. If related to 159 Squadron activities, Shores' detail confirms (emphasis mine):

However, Cherdchay's eye witnesses on the ground at Mae La Luang all describe the Ki-45 as having crash landed on an afternoon. Umemoto would not have had access in 2002 to Cherdchay's interviews since they were conducted six years later, in 2008; so if Umemoto's listing of the crash landing was addressing the Mae La Luang event, he could not have been aware of a conflict of a few hours (with a future source). The conflict affects the date he uses for the event, whether it was included with the harbor patrol, that is, in the evening before midnight, or, sufficiently later after the mission proper to have possibly occurred after midnight, ie, 13 April. The afternoon of the latter is here assumed. Unit, Casualty: As noted above, Ki-45s were the only twin-engined IJAAF fighters in the Burma Theatre and they were in Sentai 21; but, more to the point, they had two-man crews. Shinpachi[13] points out that there were single-engine Ki-51s with two-man crews operating in the Burmese Theatre; but I found no event listed by Umemoto that could be tied to that at Mae La Luang. As well, there were also single-engine two-man crew Ki-36s in the theatre, but Umemoto did not list any Ki-36 casualties which could be related to Mae La Luang.[13a] Pilot: In his accompanying narrative, Umemoto describes Lt Yasushi Ushijima as both chutai commander and the pilot who crash landed. Ushijima is confirmed on the Internet as commander of Chutai 2 of Sentai 21 which arrived in Rangoon from Palembang on 08 Mar 1943.[14] Per Umemoto, then, the chutai commander's aircraft was the first casualty in his company, only a month after arriving. Googling in Japanese, I find no mention on the Internet of Ushijima's crash landing, nor if he survived the war. Location: Rangoon is identified as the location where the plane was hit. That the plane then crash landed 270 km away in Mae La Luang is improbable (note that the 407 kph optimum speed of a Ki-45[14α] is an irrelevant detail since the plane would not have been able to travel at near that speed with only one engine). That the aircraft crash landed so far from where it was recorded as hit (Rangoon) implies that the records that Umemoto consulted were incomplete. But, regardless, it is felt that the clarity of the detail of a two-man IJAAF aircraft crashing / crash landing without fatalities in the Burma Theatre plus its occurrence on a riverbank in Mae La Luang overrides the inconsistency in hit location. Shooter: Umemoto names 159 Squadron with its B-24 Liberators, which Shores identified as flying only at night, as having shot the Ki-45 which eventually crash landed in Ban Mae La Luang, but in the daylight of afternoon per eye witnesses. In his narrative, as already noted, Umemoto acknowledges that he couldn't confirm 159 Squadron having encountered Ushijima's Ki-45; which is as it should be since 159 flew only at night. Sentai 21 reported one B-24 shot down on the same day, and two more B-24s shot down on the following day, the 13th. But Allied records show no B-24s in the air over Burma on 12 or 13 Apr 1943, much less shot down on either of those dates. While there were no B-24s in the air on those dates, there were B-25s recorded as having bombed Magwe (360 km distant at N20°09.18 E94°58.05) on 12 Apr, Myitnge bridge (400 km distant at N21°50.50 E96°04.00) and Monywa Airfield (490 km distant at N22°13.30 #95°05.62) on 13 Apr 1943.[14a] Note that these three locations were substantially farther away from Mae La Luang than Rangoon at 270 km; and therefore even less likely to have been the scene of the encounter that damaged Ushijima's plane. Shores does not mention any B-25 action on 12-13 Apr 1943. No other detail has been found of B-25 encounters with IJAAF aircraft during these attacks. If, somehow, Ushijima had encountered a B-25, perhaps a typographical error produced a B-24 instead of a B-25. Or perhaps Sentai 21 pilots, being new to the theatre, weren't familiar with the difference between the two at that point. Details: To repeat, whatever the discrepancies noted above, the unique combination of details involving:

seems to strongly relate Ushijima's crash landing with the event witnessed at Mae La Luang.

Interviews by Cherdchay Chantawan.[15] Neither product from Cherdchay was formally published: 1. Mr Som Tailom Prathrep, in 2008:[16]

2. Military aircraft that crash landed in the village of Mae La Luang.[20a] Subsequent to his interview with Mr Prathrep, Cherdchay conducted more interviews and assembled a more developed scenario. Again not published, this was translated into Japanese and put on the Internet. The interviews occasionally quote witnesses, only one of whom is identified. As translated into English:[20b]

Of Sentai 21, Shores wrote:

Shores has no entry for Monday, 12 April 1943, the date that Umemoto gives for the crash landing. Shore's entry for Tuesday, 13 April 1943, is only about a Blenheim V5445 of 60 Squadron shot down by anti-aircraft fire, apparently around Adwinbyin (which cannot be located on any currently available map).[27b]

Eye witness to the crash (current) At Ban Mae La Luang's Village 7, the local puyaiban (village headman), Udom Suja, introduced his neighbor across the soi, 85-year-old Gaun Sutinna.[28]

The aircraft was located in the grove of palms which is circled: it is estimated to be about 150m distant from the camera.[32] A larger scale map of Mae La Luang shows the crash landing site:[33]

I did not consider bushwhacking my way to the exact site for lack of time, as well as the marsh-like conditions adjacent to a rain-swollen waterway. Getting to the site should be a dry season operation and with the assistance of locals who are familiar with the ground.

Eye witness to the bell/gong described in Cherdchay's interviews

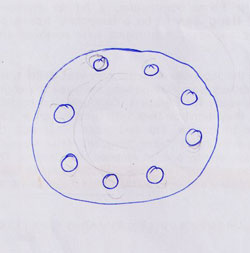

He sketched the gong and sized it at 30cm diameter and one centimeter thick. The circles just inside the perimeter are drilled holes, one of which was used to hang the gong at the station:

This is the gong identified by Cherdchay as having come from the firewall of the aircraft.[36a] A subsequent visit to the memorial hall found no gong on display, nor was the long-time attendant even aware of it, but he explained that there were numerous artifacts not yet on display for lack of space and that a major expansion of the hall was planned in the near future. During that process, the gong might be (re)discovered.[36b]

The scenario above is the result of joining information from two separate, unrelated sources: Umemoto's Japanese war records and Cherdchay's interviews with local eye witnesses. As noted above, their connection relies on what is believed to be a unique combination of these common elements:

But there are major undefined and critical details centering on the circumstances that led to the plane coming down in Thailand, comparatively far from active combat areas in Burma. The only potential concrete lead at this time depends on identifying the aluminum disk that is reputed to have been a firewall on the aircraft. And, unfortunately, the disk is, effectively, lost, but hopefully still in possession of the Thai-Japanese Friendship Memorial Hall in Khun Yuam. Without that piece of evidence, the above scenario is simply speculative, based on coincidence.

APPENDICES

As a Police Lt Colonel, he was stationed at Khun Yuam as Deputy Superintendent to the Chief of Amphoe Khun Yuam Police from 1995 to his retirement (sometime after 2004). He took it upon himself to record reminiscences of local Thai residents about events in Khun Yuam during World War II and to collect artifacts of the period from various sources. These formed the nucleus for what eventually became the Thai-Japan Friendship Memorial Hall in Khun Yuam. He was instrumental in getting interested Japanese to provide financial support for the project and made at least one trip to Japan in that effort. In the process, he became a close friend of Inoue Motoyoshi, an IJA veterinarian who had passed through Khun Yuam near the end of the war, and who hosted Cherdchay's visit to Japan.[37]

Cherdchay Chantawan, Interview with Mr Som Tailom Prathrep (2008) in Thai language. Since the interview has not been formally published, it is included here for reference (two pages).[38]

Cherdchay Chantawan, Japanese military aircraft that crash landed in the village of Mae La Luang (based on numerous interviews) in original Japanese language (English language translation above).[39]

Umemoto's listing of Sentai 21 casualties in Burma Theatre.[40] Umemoto lists four crashes of Sentai 21 aircraft in the Burma Theatre. Three of the four involved the deaths of crews. But, the earliest involved no fatalities, and also uniquely describes the location of the crash as a river. The text narrative specifies a riverbank. (see copy of page in the narrative which follows this listing).

Umemoto narrative providing more detail on the Mae La Luang crash: pages 317 and 318:[41]

This translates roughly as:[41a]

Burma Theatre in April 1943 showing Allied bases and Allied targets in Burma[42]

Allied air units with activities over Burma in 1943[43]

Extract from USAAF CHRONO showing Allied targets in Burma Theatre during the period April 01 to 15 1943 (with emphasis mine).[44] THURSDAY, 1 APRIL 1943

FRIDAY, 2 APRIL 1943

SATURDAY, 3 APRIL 1943

SUNDAY, 4 APRIL 1943

MONDAY, 5 APRIL 1943

TUESDAY, 6 APRIL 1943

WEDNESDAY, 7 APRIL 1943

THURSDAY, 8 APRIL 1943

MONDAY, 12 APRIL 1943

TUESDAY, 13 APRIL 1943

WEDNESDAY, 14 APRIL 1943

THURSDAY, 15 APRIL 1943

Contemporary map of area around Mae La Luang: excerpted from map titled "Estimated Operational Capabilities of Japanese Airfields Nov 1943", attachment to Airfield Report No 16 (Chief Intelligence Officer, HQ Southeast Asia Air Command, Nov 1943) (map: USAF Archive Reel A8055 p 0235).

Royal Thai Air Force Records No information has been found relating to the event at Ban Mae La Luang. This is possible because it did not involve RTAF personnel or aircraft. On the other hand, Mae Hong Son personnel did visit the site and provide translations between Thais and Japanese (via the intermediary of the English language), so it would be reasonable to assume that provincial officials had notified the RTAF.

|

References are provided in this column for the convenience of the reader. Please advise author of any errors. Readers are encouraged to copy this webpage for their own future reference. See How to Copy Webpages. These pages were composed to be viewed best with Google Chrome. This webpage is longer than most in this series on WW2 aircraft losses because references are not readily available to the general reader and are therefore presented in total. 1.^ This date is one day later than specified by Umemoto. The reason for the difference is explained in discussion later on this page. (梅本弘 [Umemoto, Hiroshi], ビルマ航空戦・上 [Burma Air Warfare] 第1巻 [Volume 1] (Tokyo: Dai Nippon, 2002)], p 490, entry 8) 2.^ Ban Mae La Luang: N18°31.6 E97°56.0 Map: Extract from Google Maps, annotated by author using Microsoft Publisher. 3.^ (deleted) 4.^ (deleted) 5.^ (deleted) 6.^ Extract from Google Maps, annotated by author using Microsoft Publisher.

6a.^ Taken from map titled "Estimated Operational Capabilities of Japanese Airfields Nov 1943", attachment to Airfield Report No 16 (Chief Intelligence Officer, HQ Southeast Asia Air Command, Nov 1943) (map: USAF Archive Reel A8055 p 0235). See excerpt in Appendices. 6β.^ See extract from USAAF CHRONO below. 6b.^ Named as Mesarieng (Hminelongyi). A Survey of Thailand (Siam) (Washington: War Department, 15 Mar 1941), p 28, and Appendix, p 89 (USAF Archive Reel B-1750, pp 1748 & 1811, respectively). Boonserm Satrabhaya, in his Chiang Mai and the Air War

The road improved was future Thai Route 108 between Hot and Mae Hong Son, but the improvement occurred only long after the war was over. Boonserm Satrabhaya, Chiang Mai and the Air War (Bangkok: Winyuchon, 2003) 6c.^ "Mesariang (Hmainlongyi; Hminelongyi) Emergency Landing Ground", dated 31 Dec 1944 (USAF Archive Reel A1285 p 1243).

6d.^ See first Appendices for brief summary of Cherdchay's activities.

7.^ Umemoto, ibid.

8.^ Christopher Shores, Air War for Burma (London: Grubb Street, 2005). 8a.^ ibid, p 425. 9.^ See list below extracted from Umemoto, ibid, at Sentai 21 casualties.

10.^ As noted, Umemoto, ibid, vol 1, p 490, entry 8.

11.^ Umemoto, ibid, vol 1, p 317; copy of pages from book included in Umemoto's narrative below.

12.^ Shores, ibid, p 408.

13.^ Shinpachi is an established contributor to the ww2aircraft.net Forum; his comment starts, My first impression. 13a.^ Author's response, starting, Okay, I appreciate. 14.^ 二式複座戦闘機・屠龍 (キー45改) [Type 2 double-seat fighter, dragon slayer (Ki 45)]

14α.^ Kawasaki Ki-45 Toryu.

14a.^ The Official Chronology of the U.S. Army Airforce in World War II. and see summary of Allied events in Appendix, Burma Theatre in April 1943 showing Allied bases and targets in Burma.

15.^ See first of Appendices for brief summary of Cherdchay's activities. 16.^ From: Cherdchay, Pol Lt Col Chomtawat, IJA soldiers traveling thru Khun Yuam (15 interviews) [not formally published]; พันตำรวจโท เชิดชาย ชมธวัช, บ้อมูลเส้นทาง เดินทัพทหารญี่ปุ่น ในอำเภอขุนยวม สงครามมหาเอเชียบูรพา (สงครามโลกครั้งที2), [unpaginated]. Document held in library of Chiang Mai National Museum. Thai translated by Chanagun Chitmanat, Maejo University, 03 Jun 2012. Copies of original pages in document are included in the Appendices. A translation of a broader scenario based on several more interviews, again not published, but presented originally in Japanese on the Internet, immediately follows this interview. 16a.^ One of two different time periods stated by witnesses; this being "March" without year and the other being "June-July" in 1943. 16b.^ The detail appears in both interviews. Asked about the plausibility of such a maneuver, Shinpachi, the correspondent in the ww2aircraft.net Forum, responded that it was possible "because pilots tried to help / rescue friends even at the risk of their own lives." (Old Thailand Aircrash #53). The same technique was reported by witnesses to Sgt Ono's crash landing in Omkoi on 25 Dec 1941. The feats are more plausible when one considers the pilots involved in both events were veterans well seasoned from other battle theatres. 17.^ Location not found. On 1992 RTSD map 4546II BAN MAE LA LUANG, the watercourse through Ban Mae La Luang is called "Nam Mae La Luang" while on current Google Earth / Maps, it is titled "Mae Tho". The source for the location of the aircraft's resting place, Mr. Gon Sutinna (discussed later), placed it along the river, Nam Mae La Luang / Mae Tho. 18.^ Both interviews note the use of English; and one version mentions a note dropped from a Ki-45 to the crew on the ground as being in English. 19.^ Note that there are two locations designated "Wat Si La Pha" on Google Earth. One with structures visible is at N18°31.97 E97°56.02. The other, with no ground features to be seen in the satellite view is about 600m north at N18°32.30 E97°55.95. The first has an identifying sign on the ground; at the time of our visit, we weren't aware of the second site, so we didn't check it. 20.^ This parenthetical note is in the original. We did not query the name. 20a.^ Translated from the original メーラルアン村に不時着した日本軍機, Japanese military aircraft crash landed in Mailaluan village, page 1, page 2. 20b.^ Per Google Translate; smoothed by author. 21.^ Not located. 22.^ To repeat, the other interview dates the crash as in March, with no year given. 23.^ Presumably their concern lay in an enemy, an Allied aircraft, coming from Burma which was under the control of Thailand's ally, Japan. 24.^ Again, both interviews describe this detail. This sketch appears on the Japanese language webpage. 25.^ Not identified/located. 25a.^ Wat Si La Pha: N18°31.97 E97°56.02.

26.^ As noted above, this detail is common to both interviews.

27.^ This photo appears in the Japanese language webpage. The webpage does not otherwise mention the aircraft identity. As noted below, this photo provided a shortcut for searching Umemoto's list of air events in the Burma Theatre.

27a.^ Shores, ibid, p 425.

27b.^ Shores, ibid, p 82

28.^ Photo:

29.^ (deleted)

30.^ As discussed in Note 9, the name of the river has apparently evolved from Nam Mae la Luang to Nam Pho.

31.^ Dioptra view 6122022135829.jpg, taken 12 Jul 2022, and annotated by author using Microsoft Publisher.

32.^ Note that here How to Estimate Distance Using Just Your Thumb could not be used: there were no standard objects in view with which to calibrate. So, note to file: a rangefinder might be a good addition to a field kit. 33.^ Map extracted from Google Earth Pro and annotated per eye witness information by the author using Microsoft Publisher.

34.^ Eye witness: รตต บุญเกิด คำยอด 35.^ Ban Mae La Luang Police Station: N18°31.93 E97°55.98 36.^ Thai-Japanese Friendship Memorial Hall in Khun Yuam: N18°49.84 E97°55.97

36a.^ Shinpachi questioned the size of the "gong" as not having been large enough for a firewall (ww2aircraft.net)

36b.^ Recovery of the "gong" might assist in identifying the type of aircraft that crash landed at Mae La Luang.

37.^ Photo source: frame from untitled video from Japanese TV dated 11 Dec 2007 Sources for background on Cherdchay Chamtawat: 1. Khun Yuam booklet (Thai version) per Jack Eisner email of 2258 02 Sep 2008 with translation by class project (ทหารญี่ปุ่น ไนความทรงจ่าบอง ชาวบุนยวม ในสมัย สงครามโลกครั้งที่2 โดย พันตำรวจโท เชิดชาย ชมธวัช Khun Yuam Memories of Japanese Soldiers in WW2 by Cherdchay Chomtawat ) 2. Discussions between Cherdchay and author.

38.^ From: Pol Lt Col Cherdchay Chomtawat, IJA soldiers traveling thru Khun Yuam (15 interviews) [not formally published]; ibid.

39.^ Japanese military aircraft that crash landed in the village of Mae La Luang, メーラルアン村に不時着した日本軍機1 and メーラルアン村に不時着した日本軍機2.

40.^ Umemoto, ibid, each casualty as referenced. Narratives:

41.^ Umemoto, ibid, Vol 1, p 317.

41a.^ Per Google Translate; smoothed by author. 41b.^ 159 Squadron was the only RAF unit flying B-24s at that time; however, the USAAF 10th Air Force was also equipped with B-24s: squadrons included 9th, 436th, 492nd, and 493. As noted elsewhere, the USAAF Chronology lists no B-24 action on 12 or 13 Apr 1943. See Extract from USAAF Chrono. 41c.^ This was confirmed by a review of Umemoto's listings for the period.

42.^ Map extracted from Google Maps; annotated by author using Microsoft Publisher. Small red 'burst' symbols on map represent areas hit by Allied bombers in central Burma in the first half of April 1943. A chronology of USAAF attacks for that period is included as an appendix for information. The larger red symbol is as labeled, Mae La Luang, where Ushijima crash landed.

43.^ 159 Squadron is designated by Umemoto. USAAF assignments are from Shores, ibid, pp 387, 389. Coordinates sources:

44.^ The Official Chronology of the U.S. Army Airforce in World War II.

General notes. Sentai 21 Chutai 2 = Daniel Ford describes a sentai as divided into three companies, or chutai (An Introduction to the Japanese Army Air Force). So Lt Ushijima was commander of Sentai 21 Chutai 2. Language cross-references: |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

On this date,

On this date,

Pol Sub Lt Boongird Kome-yod,

Pol Sub Lt Boongird Kome-yod,

Cherdchay Chamtawat is the source here of two documents recording numerous interviews with local Thais about the Mae La Luang crash.

Cherdchay Chamtawat is the source here of two documents recording numerous interviews with local Thais about the Mae La Luang crash.