| N18°36 E98°49 | Ban Kat (Th: บ้านกาด / Jp: バンガート村 ) page 3 of 8 |

Route 1013 |

|

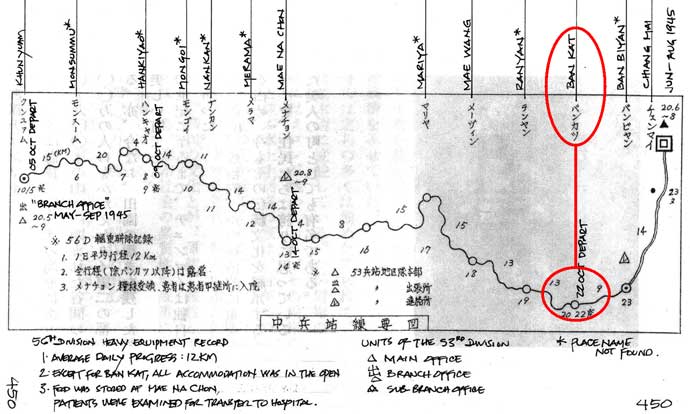

Source 2. Japanese war veterans organized an effort to recover IJA remains in Thailand, Burma, and India which got underway in 1977. The highlights of their efforts were published,[20] but there is little information about conditions at Ban Kat. It was located on the Central Route, for which the following map was provided:[20a]

|

20.^ Journal 20a.^ Journal, p 450, annotations by author in conjunction with translators. |

|

|

|

What was presented were these observations:

While Mae Na Chon was 68 km to the west, the village chief there during the war made these comments generally relevant to Ban Kat:

Source 3. The Etou Foundation (慧燈財団), in an early comment, erroneously reported: In the final stages of the war in 1945, the Japanese military withdrew from Burma and returned through this area. When many died of malaria and related illnesses, their comrades buried them in the abandoned well at the San Kayoum temple.[24] More recently, and unfortunately perpetuating that error, this author commented on the above:

Curiously, there does not appear to be any Thai research published about this location. Nov 1977 (BE 2520) Partially supported by a Japanese Government financial grant, Japanese war veterans came to Ban Kat asking where the Japanese army had stayed and where the dead had been buried. They were directed to Wat Maan. Neither Wat San Kayoum nor its well are mentioned in the final report of that effort.[26] Jan - Mar 1978 (BE 2521) The results of on-site research by the veterans were followed up by younger Japanese who retrieved what remains could be found, which eventually numbered 63.[27] Remains recovered were cremated with proper Buddhist ceremony and the ashes returned to Japan.[28] The sisters remember things differently: the remains were relocated directly from Wat Maan to the well at Wat San Kayoum. However,

would have guided the Japanese in handling the remains: a small portion of each would have been retained for proper ceremony and return to Japan, with the rest of the remains committed to the care of the well. 1989 (BE 2532) Shirabe Kanga was one of several Buddhist monks who had gone to Cambodia to help refugees. On the way back, they met relatives of Japanese war dead from Saga Prefecture, and went with them to Chiang Mai. In Chiang Mai at Wat Muen San, they met an old Thai monk who urged them to recover the remains of IJA troops The new Witayacom High School serving Ban Kat was commissioned.[30] During construction, the well was rediscovered along with its bones which had come from both local mayhem as well as the subsequent relocation of IJA remains. 1990 (BE 2533) Shirabe Kanga, motivated by the Thai monk's urging, began the search for IJA remains.[30a] 1992 (BE 2535) Per an Etou Foundation information leaflet about the memorial (as translated):

1993 (BE 2536) The Japanese found the location of the well attractive: it was remote from the development in Bat Kat in an appropriately quiet, peaceful area. An Etou Foundation English-language information leaflet about the memorial notes:

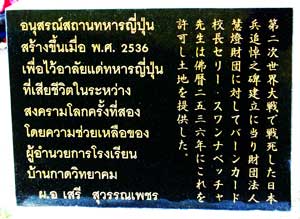

A bilingual Japanese-Thai sign at the entry point to the memorial area translates as:

1995 (BE2537) Etou Foundation was formally established by Shirabe Kanga to facilitate the collection of remains and the building of a memorial.[34] An educational assistance / scholarship program was begun in the Ban Kat schools.[35] 2001 (BE 2544) A pedestal on the left side of the bell tower written in both Japanese and Thai[36]

translates as:

2002 (BE 2545) Etou Foundation website information about the memorial tells in translation that the bell and tower were constructed in 2002.[38] Date: Ongoing Organized by Etou Foundation, Remembrance Day Services are held annually at the memorial:[39]

|

22.^ Journal, p 422

23.^ Journal, p 452

24.^ Handout brochure for memorial service at Ban Kat, unpublished (Chiang Mai, Etou Foundation, Aug 2008); translation by author.

25.^ "Review Note 2" (03 Nov 2008) in Hardcastle, David, "How Japan has not forgotten: 63 years after The War", City Life Chiang Mai (Nov 2008).

26.^ Journal, pp 419-470.

27.^ Journal, p 470 28.^ Journal, p 460 ff

29.^ Hastings, Max, Retribution (New York: Alfred A Knopf, 2008), p 78

30.^ ข้อมูลทั่วไป (general information on website, www.bankad.ac.th, now a dead link). Per Konishi email of 18 Apr 2012 (Rev 1). By 04 Jul 2012, this school info website had been expanded and historical info was available at History (link now dead). The commissioning date appears to have been 1987 (BE 2530)

30a.^ Per clarification in Konishi email of 18 Apr 2012 (Rev 1).

31.^ "Details about the Monument Dedicated to Those Left Behind in the Thai-Burma Theatre": from English language Etou Foundation handout for memorial ceremony on 24 Jul 2008.

32.^ ibid.

33.^ See section titled '2001 (BE 2544)' below, along with footnote 37. 34.^ The first edition of this web page incorrectly identified a "Masashi Yutaka" as having established the Etou Foundation. A biography, in Japanese, of Shirabe Kanga [調 寛雅(しらべ かんが)], who actually provided the impetus for establishing the foundation, is online. I will get this translated later. (Rev 1). Alas, I waited too long: the lilnk is dead. Contact information with the foundatiion was lost during the Covid pandemic (comment: 20 May 2022). 35.^ From "Etou Foundation Chronological History" in Japanese language at http://ww7.tiki.ne.p-~intuji-ensen.htm, accessed 16 Jul 2010; now unavailable 36.^ Author photo: cimg2235.jpg, 07 Jan 2008 37.^ Consistent with the Etou website's History of the Memorial in Japanese (link no longer active). 38.^ ibid 39.^ Tigerpix-uap-133.jpg, 24 Jul 2008. Courtesy of 'Gus' Gutteridge, Thaigerpics. The 2011 ceremony was covered in Japanese in detail at: NB: Google Chrome browser can automatically provide a basic translation of this link.

|